The road stretched forever. Just this thin brown line cutting through green nothing, disappearing into a horizon that never got closer. My white Hilux – already baptized by someone else’s adventures – was about to get a proper South American beating.

Jungle Highway Toward The Bolivian Border

Cusco to Bolivia. Simple enough on paper.

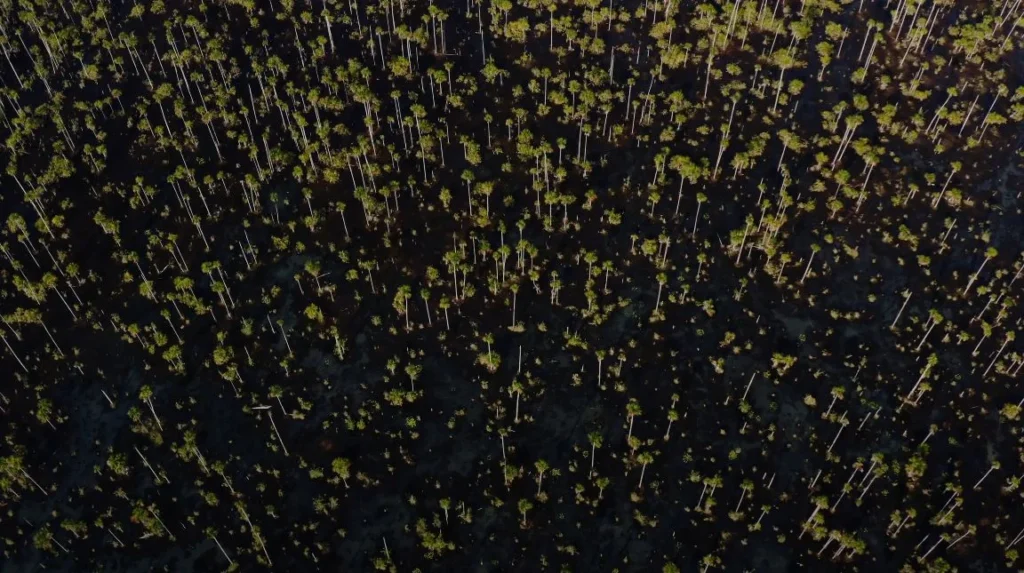

Most travelers take the tourist route. Nice asphalt. Tour buses. Comfort stops every hour. But staring at Google Earth for weeks, I kept coming back to this other line. This dirt track that shot straight through the Amazon toward the Bolivian border. No reviews. No blog posts. Just existed.

That should’ve been my first warning.

The Reality Check List:

- Distance on map: 487km

- Actual distance with detours: 600km+

- Google’s time estimate: 8 hours

- Real time: 2.5 days

- Number of rivers crossed: 7

- Number of bridges: 2

- Times stuck in mud: 3

- Spare tires used: 1

Started before dawn. The last gas station clerk in Quillabamba looked at me funny when I said where I was headed. “Por allá?” That way? He pointed vaguely southeast. Then sold me four extra jerry cans without being asked.

When Pavement Becomes Memory

Seventy kilometers out, the asphalt just… stopped. No warning. No gradual degradation. One second smooth road, next second my spine was trying to escape through my skull as the truck hammered over corrugated dirt.

The capybaras showed up around kilometer 200. Just there, beside the track, like someone had placed the world’s largest rodents as roadside decorations. Stopped the truck. Had to. You don’t just drive past capybaras without acknowledging their magnificence. One looked at me with this expression of supreme indifference. We understood each other.

Then the rain hit.

Not normal rain. Amazon rain. The kind where you can’t tell if you’re driving through weather or underwater. The dirt turned to cake batter in minutes. Brown, sticky cake batter that grabbed my tires and wouldn’t let go. First gear. Wheel spin. Nothing.

Spent that night in the truck at a makeshift river crossing. No lights except my headlamps. No sounds except things I didn’t want to identify.

Lake Titicaca

Three days later, different universe entirely.

Lake Titicaca doesn’t prepare you. One moment you’re grinding up another brown hillside, next moment this impossible blue stretches to the horizon. 3,812 meters up. Your lungs notice immediately. Every breath feels like you’re borrowing it.

The Floating Border

San Pedro de Tiquina is where things get interesting. It’s not really a town. More like a collection of boats pretending to be a ferry service. Your vehicle goes on what I can only describe as two canoes held together with hope and fraying rope.

| Border Crossing Reality | What They Tell You | What Actually Happens |

| Ferry Cost | 15 Bolivianos | 15-50 depending on mood |

| Crossing Time | 10 minutes | 17-45 minutes |

| Safety Equipment | Life jackets provided | You better swim good |

| Vehicle Security | Professionally secured | Three ropes and prayer |

| Operating Hours | 6am-6pm | When someone shows up |

Watching my Hilux float across this ancient lake on what looked like a raft built by optimistic children? That’s a specific flavor of terror. The boat captain smoked the entire crossing. Just stood there, one hand on the outboard motor, cigarette dangling, like this was his morning coffee routine.

Bolivia Announces Itself

The Bolivia side hit different immediately.

First thing: school parade. Where did these kids come from? Suddenly drums everywhere. Blue and white uniforms marching past while my truck was still dripping lake water. One kid broke formation to wave at me – this huge grin like he’d just seen something exotic. Maybe he had. How many muddy gringos in beaten Hiluxes roll through here?

The mountains change personality at the border. Peru’s peaks feel ancient, weathered smooth. Bolivia’s mountains are teenagers – all sharp edges and attitude. That road climbing toward La Paz? Someone drew it during an earthquake.

A woman with her horse appeared at a viewpoint. Traditional dress – those layered skirts, bowler hat at that impossible angle that defies physics. “Photo?” Five Bolivianos. I gave her ten, didn’t take the photo. She looked at me like I’d just broken some fundamental rule of tourist-local interaction. The horse looked personally offended.

The Altitude Mathematics

The Climb to La Paz:

- Start: Lake level (3,812m)

- First pass: 4,200m (unnamed)

- Second pass: 4,496m (still unnamed)

- Third pass: 4,700m (they don’t name them up here)

- La Paz rim: 4,100m

- La Paz bottom: 3,600m

- Your breathing capacity: 40% of normal

- Truck’s power: Maybe 50%

- Will to continue: Questionable

At 4,700 meters, clouds sat below me. Actually below. Like an ocean of white with mountain islands poking through. Pulled over where the road widened slightly – just enough space between the mountain wall and the nothing-drop.

Wind up here doesn’t blow. It attacks. Cuts through whatever you’re wearing like you’re naked. But you stand there anyway because when else will you be above the clouds?

The Storm That Almost Ended Everything

Four thousand meters up, the weather turned psychotic.

Started as drizzle. The annoying kind that doesn’t justify wipers but smears your windshield into blindness. Within minutes, the drizzle became a wall. Not rain falling – rain existing in every direction simultaneously. Visibility dropped to maybe three meters. Maybe.

The clay road turned into grease. Red, slippery grease that had it’s own agenda. The Hilux started sliding sideways. Not dramatically – just this slow, inevitable drift toward the edge that no amount of steering could fix. Engine screaming in first gear. Wheels spinning. Going nowhere except sideways toward a drop I couldn’t even see anymore.

Mountain Storm Survival Kit:

- Patience: 5 hours’ worth minimum

- Colombian reggaeton on USB: Essential

- Coca leaves: For altitude and nerves

- Sense of humor: Non-negotiable

- Phone signal: Don’t make me laugh

- Spare underwear: You’ll understand

Stopped. Had to. Just sat there in the truck, rain hammering the roof like bullets, waiting. Three Bolivian trucks passed me during those hours. Each driver looked at my Hilux, looked at me, shook their head. Universal gesture for “tourist.“

La Paz Drops You Like a Stone

La Paz doesn’t gradually appear. It attacks you.

You’re driving along this high plateau, mountains everywhere, then suddenly the earth opens up. The city sits in this massive bowl carved into the planet. Houses stacked on impossible angles. Roads that shouldn’t exist. The whole thing looks like someone poured a city into a hole and wherever it stuck, that’s where people live.

The descent takes forty minutes. Forty minutes of first gear, brakes smoking, praying to gods you don’t believe in. My ears popped seven times. The temperature rose 15 degrees. By the bottom, I was sweating through my jacket while snow still capped the rim above.

| La Paz Vertical Reality | |

| Rim elevation | 4,100 meters |

| City center | 3,600 meters |

| Vertical drop | 500 meters |

| Road gradient | Up to 17% |

| Brake failure points | Every 200 meters |

| Number of saints invoked | All of them |

The High Desert Nobody Warns You About

Past La Paz, Bolivia shows it’s real face. The Altiplano.

Imagine Mars, but brown. And cold. And at altitude that makes your brain stupid. The road shoots straight across this endless plateau toward the horizon. No trees. No anything. Just brown earth meeting blue sky in a line so sharp it hurts.

Stopped for fuel in Patacamaya. If you can call two pumps and a shack “fuel.” The attendant filled my tank while chewing coca, never making eye contact. Wind blew dust devils across the road. A dog slept in the middle of everything, completely unbothered. When I paid, the attendant finally looked at me. “Uyuni?” he asked. I nodded. He laughed. Not encouraging.

The Road That Tests Your Sanity

Two hundred kilometers of nothing. Actually nothing. Not boring nothing – aggressive nothing. The kind of empty that makes you question reality.

Altiplano Driving Stages:

- Hour 1: “This is beautiful“

- Hour 2: “Still beautiful but… same“

- Hour 3: “Did I pass that rock before?“

- Hour 4: “The mountains are moving“

- Hour 5: “The mountains are definitely moving“

- Hour 6: “I should’ve taken the bus“

Met a cyclist. Just there, in the middle of nothing, pedaling against wind that could strip paint. Pulled alongside him. German guy, maybe 60, looking like leather that had learned to ride a bike. “Where you going?” I asked. “Argentina,” he said. Like it was the corner store. We rode together for a minute – me at idle, him at maximum effort. Then I waved and pulled ahead. Watched him shrink in my mirror until he was just a dot against brown infinity.

When Salt Replaces Reality

First glimpse of the salt flats comes when you’re not ready. You top another brown rise, expecting more brown and suddenly white. Blazing, impossible white stretching to mountains that look painted on the horizon.

Uyuni town itself? Dusty waystation pretending to be a city. Every building sells the same thing: tours to the salt flats. Every restaurant serves the same menu: llama meat and quinoa soup. Every hotel has the same review: “Better than sleeping in your car.“

The Salt Flat Infinity

Dawn on the Salar de Uyuni. Different planet entirely.

Drove out before sunrise, following GPS tracks from someone else’s adventure. The salt crunched under tires like snow but sharper. Ten kilometers out, no reference points left. Just white meeting sky. Could’ve been driving on clouds.

The sun came up orange and violent. Shadows stretched forever. The Hilux’s shadow looked a kilometer long. I stopped, killed the engine. Silence so complete my ears rang trying to hear something.

| Salar de Uyuni Statistics | Reality |

| Size | 10,582 square kilometers |

| Salt depth | 10 meters |

| Elevation | 3,656 meters |

| Flatness variation | 1 meter over entire surface |

| Temperature range | -20°C to 30°C |

| Number of times you’ll think you’re lost | Constant |

| Actual chance of getting lost | High |

Met a tour group out there. Twenty tourists in matching sunglasses taking perspective photos with dinosaur toys. Their guide saw my muddy Hilux, my week-old beard, the coca leaves on my dashboard. “Solo?” he asked. I nodded. “Loco,” he said. Crazy. But he smiled when he said it.

The Border That Barely Exists

The Bolivia-Chile border at Ollaguë makes you question what borders mean.

One building. Two flags. Three officials playing cards. They looked annoyed when I showed up, like I’d interrupted something important. Stamped my passport without looking at it. The Chilean side was the same building, just the other half. Same officials, different uniforms. Maybe the same card game.

The Descent to Madness

Chilean roads after Bolivia feel like cheating. Smooth asphalt. Guard rails. Signs that make sense. But the Atacama Desert doesn’t care about your comfort.

Nothing grows here. Not “barely anything” – literally nothing. Mars looks fertile compared to this. The road drops from 4,000 meters to sea level in 180 kilometers. Your ears pop so much they give up. The temperature rises from freezing to 35°C. The Hilux’s engine, traumatized by altitude, suddenly remembers what oxygen is.

Desert Realizations:

- You can drive 100km without seeing life

- Not even bacteria bothers here

- Your water consumption: 4 liters per day

- Amount you brought: 2 liters

- Nearest anything: Hours away

- Cell signal: Theoretical concept

San Pedro de Atacama appeared like a hallucination. Palm trees. Actual water. Tourists in clean clothes speaking languages that weren’t Spanish. Restaurants with menus in English. Craft beer. Wifi that worked.

Felt wrong after two weeks of dirt and altitude and coca leaves. Like I’d accidentally driven into someone else’s vacation.

What The Journey Actually Teaches You

Sitting in San Pedro, Hilux finally washed, beers deep into processing what just happened, some things became clear.

The tourist route exists for a reason. It’s safe. Comfortable. Predictable. You’ll see what you’re supposed to see, photo what you’re supposed to photo, story what you’re supposed to story.

But that trans-Amazonian track? That altitude-sickness-inducing mountain pass? That salt flat where you could die fifty meters from your car and nobody would find you for weeks?

That’s where South America tells you it’s real stories.

Met a local in Uyuni who said something that stuck: “Tourists come to see Bolivia. But Bolivia doesn’t care if you see it or not. It just is.“

Final Tallies:

- Total distance: 3,847 kilometers

- Days on road: 16

- Flat tires: 2

- Altitude sickness episodes: 4

- Times genuinely lost: 7

- Money spent on gas: $400+

- Money spent on coca leaves: $3

- Value of coca leaves: Priceless

- Photos taken: 1,400+

- Photos worth keeping: Maybe 50

- Moments that changed perspective: Countless

- Desire to do it again: Immediate

The Hilux still carries Bolivian mud in places I’ll never clean. Good. Some dirt should stay.

Next time someone tells me about their “adventure” from Peru to Bolivia on a tour bus, I’ll nod politely. But I’ll be thinking about capybaras in the Amazon twilight. About clouds below mountain passes. About that German cyclist still pedaling toward Argentina. About silence so complete on white salt that you can hear your own blood.

That’s the South America they don’t put in guidebooks. The one you have to earn with bad roads and thin air and nights in your truck wondering what you’ve gotten yourself into.

Worth every terrifying, exhausting, spectacular kilometer.