It hurts the cobblestones more when you are dragging a suit case behind you at 8 AM.

It was the first time that I was in Old San Juan, not in the airport, not in the taxi-stand, but on Calle de las Monjas looking at a black sedan make its way round a massive mango whose roots had taken half the width of the roadway. The pilot was not even frustrated. Just waited, as though it was Tuesday morning. Of which, I would know, it was certainly.

Three days spent here taught me that Old San Juan has its logic. Admittedly, it is the most popular place in Puerto Rico, and it is flooded by cruise ship passengers holding maps and seeking the ideal Instagram image. Scratch the surface of the tourist and you will find a place where 500-year-old fortifications still dictate the daily life, the source of the best gelato is an Italian woman who had been perfecting her trade over decades and where taking a stroll to breakfast turn into a lesson in the colonial structures, the Puerto Rican identity today and the art of walking around with horses on the streets.

Fortifications That Still Command Respect

El Morro: More Than a Pretty Lighthouse

Walking up to Castillo San Felipe del Morro on my second morning, I understood immediately why Spanish engineers chose this spot. The thing just dominates the northwestern tip of the islet. Not in a showy way – it’s not trying to impress tourists. It’s built to control shipping lanes and 400 years later, you can still feel that purpose.

The National Park Service ranger leading our tour – a guy named Carlos who’d grown up in San Juan – dropped some context that stuck with me. “Every major power that wanted Caribbean control had to deal with this fortress first,” he said, gesturing toward the lighthouse. “Britain tried twice. Pirates tried constantly. They all learned the same lesson.”

Inside the main courtyard, the scale becomes obvious. Those yellow walls aren’t just aesthetic – they’re 18 feet thick in places, designed to absorb cannon fire. Walking through the soldier quarters, I kept thinking about the guys stationed here during the Spanish-American War. Hot, isolated, watching American ships approach from the same ramparts where their predecessors had watched British vessels two centuries earlier.

The lighthouse itself, rebuilt several times, still operates today. Coast Guard maintains it, though ships now rely more on GPS than visual navigation. But standing up there at sunset, watching container ships pass through the same waters where Spanish treasure galleons once sailed, the continuity hits you.

San Cristóbal: The Fortress Most Tourists Skip

Castillo San Cristóbal sits on the opposite end of Old San Juan, guarding against land-based attacks. Most visitors hit El Morro and call it done, but that’s a mistake. San Cristóbal is where you really grasp the defensive strategy.

The Spanish built this place to be a maze. Multiple levels, interconnected tunnels, defensive positions that could hold independently even if sections fell to attackers. I spent an hour just wandering the upper battlements, trying to imagine coordinating a defense across this massive complex.

What struck me most was the engineering precision. Every angle calculated, every wall positioned to provide crossfire support. The tour guide mentioned that during World War II, the U.S. military used parts of the fortress for training exercises. American soldiers learning urban warfare tactics in spaces designed by Spanish military engineers centuries earlier.

The views from San Cristóbal show you modern San Juan spreading inland – high-rises, highways, the airport in the distance. But from inside those stone walls, looking through embrasures designed for cannons, the perspective shifts. You’re seeing the same sightlines Spanish soldiers monitored for 400 years, watching for threats that might emerge from the interior of the island.

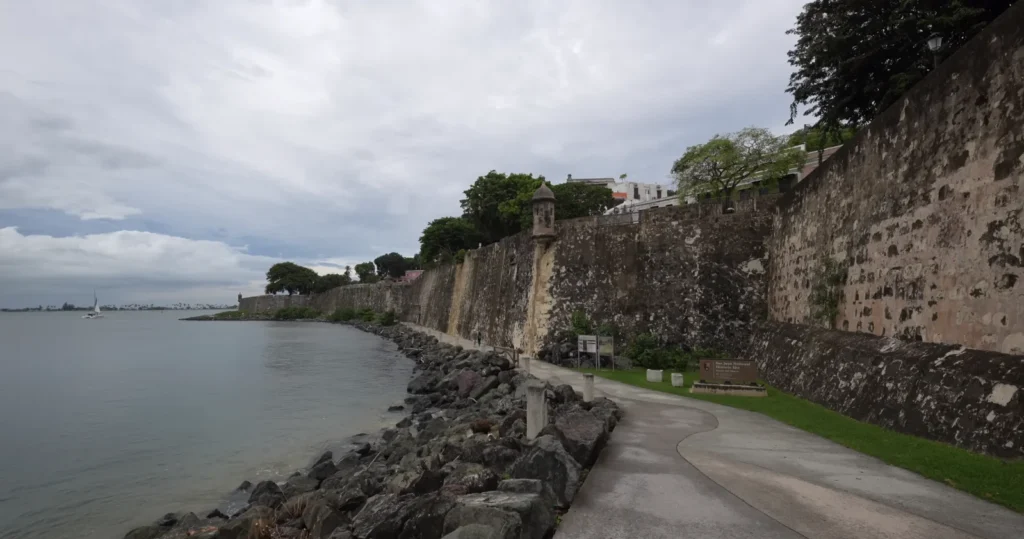

The Walls That Define Everything

The fortification walls connecting these fortresses aren’t just historical artifacts – they’re the reason Old San Juan feels like a separate city within the city. Walking along the seawall that evening, I met a local artist named Maria who was sketching the sunset. She’d lived here her whole life and when I asked about the walls, she laughed.

“These things dictate everything,” she said. “Where we park, where we walk, how we get home after a night out. Tourists see them as decoration. For us, they’re infrastructure.”

She was right. The walls force all vehicle traffic through specific entry points, creating natural pedestrian zones. They protect buildings from hurricanes and storm surge. They define property lines, create microclimates and provide foundations for newer construction. Five centuries later, Spanish military engineering still shapes daily life.

Cultural Heartbeat and Authentic Flavors

Where Locals Actually Eat Breakfast

No longer mind your continental breakfast in your hotel. Mornings in Real San Juan begin at La Mallorca, since 1848 it has been serving the same pastries. I just fell over it on my first morning attracted by the scent of fresh bread and the appearance of locals queueing at the counter.

I was addicted to the quesito – a pastry that is filled with sweet cheese and has powdered sugar on its face. Not because it is exotic or Instagram envy worthy of it, but because it is ideal at 7 AM and up with a good Puerto Rican coffee. The lady at the counter who was most likely in her sixties remembered my order after two days. She addressed me as “El americano que hablaba Espanol. The Spanish speaking American.

What I had liked the most about La Mallorca was not the food, but that was very good too. It was the rhythm of the place. The workers who build the constructions taking the café con leche to the sites. Government workers around the office talking about plans on weekends. Old people reading newspapers and discussing politics in Spanish so fast that I could have understood only half of what they were saying.

Here is where you realize that Old San Juan is not a museum. It is a neighbourhood where people can live, work and get their mornings off with pastry and coffee, as their grandparents did.

Pigeon Park: Chaos and Community

Parque de las Palomas sounds ridiculous on paper. A park dedicated to feeding pigeons. Tourist trap written all over it. But watching that dad from Lake Powell – I could tell by his t-shirt – stand calmly while his kids got swarmed by what looked like a thousand pigeons, I realized this place serves a different function.

It’s pure joy.

The pigeons in this case are pathetically overly cordial to the point that they have been fed all decades by strangers. Children scream with joy having birds on their heads. Parents take photos. Lovers spend time together in silence on benches with the bay. The huge tree that occupies the park offers some shade which is invaluable in the Caribean heat.

However, this is what guidebook failures to inform you: this space is also used by locals. I observed old men playing dominoes and teenagers meeting after school and families holding impromptu picnics under that tree. The attraction is the pigeons, yet the community makes it work.

Street Art, Identity and Surprising Revealation

The Door That Says Everything

Guidebooks do not always contain the most important things.

The door with graffiti and stickers and a hand-painted Puerto Rican flag that I saw was in a side street, where I lost my way (once again). ATM, random phone numbers, Mickey Mouse stickers, political slogans in Spanish, announcements of love and right in the middle: THE WORLD IS WAITING YOUR.

An example is a local man who was passing by me taking pictures and came to talk. Quite a long time that door has been that way, they said. People contribute to it, graffiti is drawn over, new graffiti is added. It’s like… our bulletin board.”

This is Puerto Rico in 2024. Part of America, part Caribbean Island, part whole it is. The flag in that door is not just ornamentation, but a declaration of place, a declaration of belonging to a place that lies in between official categories.

Barrachina: Sightseeing or Dumpster?

Barrachina claims to be the birthplace of the piña colada. Bold statement. Also probably unprovable, since half a dozen places in San Juan make the same claim. But you know what? After three rum-soaked days wandering these streets, I stopped caring about the historical accuracy.

What matters is this: the courtyard.

Tucked behind Fortaleza Street, Barrachina’s interior opens into this lush tropical space that feels completely removed from the tourist chaos outside. Massive palm fronds, carefully maintained planters, that perfect balance of shade and filtered sunlight. I ended up here by accident on my second afternoon, escaping a sudden downpour and stayed for two hours.

The piña colada arrived with the requisite tiny umbrella – tourist theater, sure, but effective tourist theater. Sweet, strong and cold enough to justify the markup. But the real discovery was watching the staff work. These weren’t actors playing Caribbean restaurant workers. The bartender chatting with regulars in rapid Spanish, the server who remembered that the elderly couple at table six always wanted extra ice – this was a real restaurant that happened to cater to tourists, not the other way around.

The mofongo with shrimp sealed the deal. Fried plantains mashed with garlic, topped with massive gulf shrimp in a sofrito sauce that had actual depth. Not hotel food trying to be Puerto Rican, but Puerto Rican food that happened to be served in a place tourists could find.

Word of advice: come during the 3 PM lull. Cruise ship crowds clear out, locals drift in for late lunch and you get the courtyard to yourself.

Anita Gelato: When Italian Meets Caribbean

Sometimes the best discoveries happen because you’re lost and need air conditioning.

I’d been wandering the residential streets behind the cathedral, trying to find a shortcut back to my hotel, when I spotted the Anita Gelato sign. Italian gelato in 500-year-old San Juan seemed random enough to investigate.

Anita herself was working the counter – Italian woman, maybe fifty, who’d moved to Puerto Rico fifteen years earlier and decided to bring real gelato with her. Not American ice cream pretending to be gelato, but the real deal. Slow-churned, dense, served at the proper temperature with the proper paddle.

The flavor combinations told the story: traditional Italian bases with Caribbean influences. That pistachio was straight Sicily, but the coconut-rum variation was pure Puerto Rico. The chocolate-hazelnut played it safe, but the mango-passion fruit was bold enough to work.

What got me was Anita’s approach. She’d adapted to local tastes without abandoning her craft. The tropical flavors weren’t gimmicky – they were seasonal, made with fruit from the island, executed with the same precision as her stracciatella.

“People here, they know good food,” she told me while I worked through a two-scoop cone. “You cannot fake it. Either you make it right or you go home.”

The gelato was perfect. Dense, clean flavors, that slight chewiness that distinguishes real gelato from ice cream. But sitting in her small shop, listening to her talk about adapting Italian traditions to Caribbean ingredients, I realized I was witnessing something larger – how food culture actually evolves when people move and create something new without losing what made the original special.

Sacred Spaces and Cultural Memory

Cathedral: More Than Sunday Service

The Cathedral Basilica of Saint John the Baptist occupies the center of Old San Juan, like the cathedrals are meant to: it is impossible to overlook it because it attracts all the attention. However, it was not the architecture, which was impressive as it was. It was learning that it is still being used as a neighborhood church.

My second evening I crept in with evening mass, not to serve my religious purpose but because the doors were open and the singing could be heard in the street. It was almost overwhelming, the baroque interior, with its ornate gold leaf design, its high arches, its stained glass taking the last sun-rays. This is how Spanish colonial power appeared at its highest.

But the congregation brought it all down. Women in lace head wearings, mothers with fidgety children, youths checking mobile phones during the sermon. Ordinary parish life that was occurring in an area that should have been in a museum. The service was conducted in Spanish, and the priest used local politics, local issues, hurricane recovery attempts that occurred several years before.

Following mass, I talked with one of the elderly parishioners in the name Carmen who had been in the services at the parish sixty years. She said, “My grandmother brought me here when I was a kid. Probably the same thing was done by her grandmother. The building is replaced – they fix up, mend broken hurricane-damage – but the society is the same.

Las Americas Museum: Things They Don’t Teach in School

The second floor of the former military barracks at El Morro is occupied by the Museo de Las Americas. The vast majority of visitors do not even bother to visit it and are already engaged in the fortress itself. That’s their loss.

This location narrates the history of the native cultures of the Caribbean prior to Columbus, the colonization and the centuries that followed. Not the sanitized version they serve in cruise ship talks, but the multifaceted, frequently violent reality of culture clash and struggle.

The native and original peoples are hit the most. Bronze statues around a traditional home, everyday life utensils, descriptions of farming methods and social orders. The most amazing thing was that very few people in America including myself are aware of the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Caribbean. The Taaiino were not the primitive people awaiting the arrival of the Europeans. They also possessed advanced agricultural practices, trade routes, artistic cultures that gave rise to all those that followed.

The contemporary culture section brought things into the present – Day of the Dead altars, Caribbean music evolution, the ongoing influence of African traditions brought by enslaved peoples. This wasn’t ancient history sealed behind glass. These were living traditions, adapted and evolving, still shaping Puerto Rican identity.

Standing in that museum, looking at artifacts and artworks spanning five centuries, I understood something crucial about Old San Juan. It’s not preserved colonial architecture serving as backdrop for tourist photos. It’s a place where different cultural streams – indigenous, Spanish, African, American – have been mixing and creating something new for 500 years.

La Fortaleza: Power and Symbolism

La Fortaleza has served as the governor’s residence since 1533, making it the oldest executive mansion in continuous use in the Americas. You can’t tour the interior – it’s still the working residence of Puerto Rico’s governor – but the exterior tells it’s own story about power, colonialism and the complicated present.

The building itself is stunning – pristine white walls, perfectly maintained grounds, that view over San Juan Bay that probably influenced more political decisions than anyone wants to admit. But what fascinated me was watching the security detail, the government vehicles coming and going, the reminder that this beautiful colonial building still houses real political power.

Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States plays out daily in these streets. American citizens who can’t vote for president. A territory with it’s own constitution but limited sovereignty. Federal laws that apply unevenly. Standing outside La Fortaleza, watching American and Puerto Rican flags fly side by side, you feel the complexity of that relationship.

Raíces Fountain: Memory in Bronze

The Raíces Fountain next to the capitol building is likely photographed thousand times a day. The three cultural sources of Puerto Rican identity, TaTaino, Spanish, and African are depicted in bronze figures which were placed in a circle around a fountain with the American and Puerto Rican flags waving above it.

It is street art that has one point to make, evidently. However, observing families taking pictures of each other here, children playing in the fountain spray and parents telling them how important they were seems to me to be how symbols could be used in every day life. This was not only tourist infrastructure. It was a sanctuary where Puerto Ricans took their children to discuss identity, heritage, complicated history of how various people came up with something new together.

The fountain has many functions, which include tourist attraction, civic symbol, meeting place and the subject of numerous family snapshots. It is practical as well as burdened by history like all things in Old San Juan.

Final Thoughts: What Old San Juan Actually Teaches You

Standing on the city walls that final evening, watching the sun drop toward the horizon while container ships navigated the same waters Spanish treasure galleons once used, I realized something about travel writing.

Most articles about Old San Juan focus on the Instagram moments – those perfectly preserved colonial facades, the dramatic fortress views, the cobblestone streets that photograph beautifully. All true, all worth seeing. But missing the point entirely.

What makes this place remarkable isn’t the preservation of the past. It’s how the past continues to shape the present in unexpected ways.