The first thing I remember clearly is the way the tracks bent toward the mountain.

I was standing just behind the driver, watching the rails slide out in front of us and there was Fuji at the end of the line, too perfect to feel real. Through the front window it didn’t look like scenery, it looked like a screen saver someone had forgotten to turn off. Houses, power lines, crossing signs all of that jittered past, but the mountain stayed still, just sitting there, patient.

On the platform at Fujisan Station, the mood changed from cinematic to ordinary almost immediately.

People were doing very normal things: checking a timetable, scrolling on their phones, adjusting a scarf. Only if you looked up over the fence, past the modest sign for “FUJISAN STATION HOTEL,” did the white triangle appear again, floating behind rooftops. The kind of view you’d kill for in most cities was just… background here.

By the time I reached Kawaguchiko Station, the day had sharpened into that particular winter blue Japan does so well.

The station building itself looks like it’s trying to behave, half-European, half-Alpine lodge, with a clock in the gable and Fuji looming directly behind. People streamed out with rolling suitcases and camera bags. Some of them stopped and posed immediately; others, maybe on their second or third trip, just walked straight past, like the mountain was an old colleague they didn’t need to greet.

I wasn’t in any rush. I just stood there for a minute on the edge of the bus bay, letting the cold bite my fingers and watching the mountain watch back.

A little later, I ended up in The Park Coffee Stand, a wooden box of a café tucked close enough to the lake that everyone was still wearing outdoor clothes at their tables.

Inside, the air was warm and smelled of espresso and something buttery from the griddle. Staff in navy aprons moved quickly between tables, the black-and-white sign — THE PARK — cutting the room in half. It felt like the sort of place that didn’t exist ten or fifteen years ago, but now you can find in almost every scenic town: third-wave coffee, wood panels, people quietly editing photos of the landscape they’ve just come in from.

Fuji wasn’t visible from where I was sitting, but it didn’t need to be. You could tell it was out there from the way everyone’s phone galleries looked when they tilted them toward each other white peak, blue sky, again and again, in slightly different compositions.

A Forest That Refuses to Perform

Later on, the scenery narrowed.

The path into Aokigahara was nothing dramatic at first just a dirt trail under leafless branches, the kind of winter forest you could find in a dozen other countries. The further you look into the frame, though, the more everything seems to close in: trees leaning at odd angles, branches knitting together overhead, ground thick with a dull carpet of needles and last year’s leaves.

Aokigahara sits on old lava flows on Fuji’s northwest flank, which gives it that uneven, porous ground and dense, scrambling growth you see in photos and guidebooks.

describes a promenade of walking paths cut through what is essentially a virgin forest formed after eruptions centuries ago.

You can feel that age, even in a simple shot like this. The trees aren’t beautiful in any romantic sense; they’re just there, indifferent. No grand viewpoints, no “photo spot” sign, just a corridor of muted browns and greys. It’s the opposite of Fuji’s clean, graphic triangle.

Everyone knows the other reputation this place has and it hangs over the forest heavily in international coverage. Recent articles lean into the darker side, pointing out it’s status in the public imagination as “Japan’s suicide forest,” and the tension between tragedy, folklore and tourism. But standing on that path or even just looking at it again on screen what sticks with me isn’t horror. It’s the quiet.

There are no people in this frame. No overhead cables, no vending machines, no small white van trying to squeeze past you, the usual constants of Japanese travel. Just the path, full of small pinecones, curving out of sight. The sort of place you walk into thinking about one thing and walk out thinking about something else, unsure exactly when the shift happened.

The forest doesn’t try to impress. It doesn’t offer you much narrative either. It just swallows sound and waits for you to decide what you want from it.

Smoke, Skewers and the Slow Business of Eating Around Fuji

The first real warmth in the day came from food.

Not from a restaurant, at least not at the beginning, but from a stall where skewered squid were being turned over hot metal.

Two hands, steady and practiced, rotate the skewers above a wire mesh grill. The squid are lacquered in sauce, catching the light in oily streaks, steam rising around them. To the right, a foam box is packed with raw squid lined up in military formation, each pierced through with a stick and waiting it’s turn over the coals. There’s a spray bottle in the corner, some anonymous plastic container, nothing carefully styled for photos just a working stand, mid-shift.

The smell, even in memory, is heavy: sweet soy, a bit of char, sea still clinging on. It’s the kind of snack that feels exactly right in this setting. Fuji in the background somewhere, the air cold enough that your fingers sting and in the middle of it all, something hot and a little messy on a stick.

Just along from here, the mood softens.

This ring of dango looks almost ceremonial: pale rice dumplings lined up around an open brazier, each skewer stuck into the ash so the rounds face the embers. Some have already browned, catching small freckles of color; others are still smooth and white, waiting. It’s an image of patience. Nothing rushed, nothing plated with tweezers. Just skewers turned slowly until they’re ready for whatever comes next sweet soy glaze, maybe or kinako.

A second stall makes the options even clearer.

Here the dango are already finished, each skewer resting in a wooden rack with handwritten numbers beneath. One is buried under a thick, pale-green topping. Another wears dark, drizzled stripes. The plain ones look almost shy by comparison. The price tags are simple, a little weathered, taped to the beams above: ¥500, ¥600. Nothing about this feels curated for tourists; it’s just straightforward, almost matter-of-fact temptation.

Later in the day, the food becomes heavier, more structured.

A cast-iron pot lands on the table, full of thick, miso-colored broth and wide, homey noodles almost certainly hōtō, the local Yamanashi specialty, usually loaded with pumpkin and vegetables and served bubbling hot.

mention it as the dish meant to restore you after long days in the cold around Fuji.

Around the pot: a bowl of white rice, a small salad with a wedge of tomato, a side plate of lightly fried fish or vegetables, bright yellow pickles and a dab of pale sauce on a separate dish. Everything rests on a black tray, the lacquer holding small reflections of the overhead light. It’s not an extravagant meal, but it radiates a kind of solid, local generosity. After walking in the wind off the lakes, you want something exactly like this: blunt, warm and unapologetically filling.

For lighter cravings, there’s a counter that looks almost like a bakery until you read the signs.

Rows of golden sticks shrimp rolls, mixed-seafood fritters, potato-and-butter combinations line red racks behind clear glass. Each one has a small card with neat Japanese text and a matter-of-fact English translation below: “Clams, Shrimp, & Japanese onion,” “Squid, Carrot, Cloud ear mushroom, Onion, Lotus root & Shellfish.” This is Maruten, a specialty outlet for fried fish cakes and tempura-like skewers, the sort of place where people agonize briefly between choices and then walk off with something too hot to bite into immediately.

Between these stalls and shops, eating around Fuji becomes a slow rhythm more than an itinerary.

You walk a bit. The mountain appears between buildings. You notice the smell of charcoal or miso. You stop. You eat something on a stick or out of a heavy bowl. You keep moving.

The Shrine That Used to Be the Starting Line

The approach to Kitaguchi Hongu Fuji Sengen Shrine doesn’t really begin at the torii. It starts further back, where the gravel path opens between tall cedar trunks and the stone lanterns begin to repeat themselves into the distance.

In the photo, the lanterns on the right are softened with moss, leaning slightly, as if they’ve been listening in on centuries of footsteps. People drift through the middle of the path in winter coats; no one looks rushed. Far ahead, the main gate is a small red shape at the end of the corridor.

Historically this shrine was one of the starting points for pilgrims climbing Fuji via the Yoshidaguchi trail, the old northern route up the mountain. These days most climbers cheat by taking a bus to the 5th Station, but the shrine is still recognized as part of the Mount Fuji UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site, a formal acknowledgement of it’s role in the mountain’s spiritual story.

Up close, the sacred cedar dominates everything.

The trunk is so wide it looks like it belongs in a different scale of forest altogether. A thick shimenawa rope wraps around it, tied in a heavy bow, white paper shide hanging down. Next to it, a wooden sign announces it’s age in characters I can’t fully read but understand anyway: a thousand years. That number appears in guidebooks and tourism blurbs, but seeing the tree’s skin rough, layered, almost geological makes it feel less like a statistic and more like a shrug. Of course it’s that old. Why wouldn’t it be.

The shrine buildings themselves are painted in a shade of red that deepens in the forest light.

The main hall sits slightly elevated, black railing and gold accents catching what’s left of the afternoon. To the side, a torii gate and stone steps lead up into another pocket of trees. Red banners cluster on the left like a small crowd that never leaves. When I first saw this, it didn’t feel like a “sight” so much as a place still at work a node in a network of rituals that happens to accept visitors with cameras.

Further inside the grounds, a simple stone bridge crosses a narrow channel of water.

In that frame, a small group is walking across, talking to each other, not paying much attention to where they are. I like that about shrines in Japan: people use them. They cut through them on the way somewhere else, they meet friends there, they bring kids who don’t care about history but like the echo of their footsteps on the stone.

If you step back again, out toward the large torii, the shrine becomes a threshold more than a destination.

The gate stands against a clean winter sky, shrubs and lanterns around it’s base. It marks the line between town and sacred space, but in practice the line is blurry. You can see ordinary buildings and parked cars just beyond the trees. Old accounts talk about pilgrims starting their climb from here, walking for hours before even reaching the slopes of Fuji.\

Now, most of us just come to look, breathe the cedar air and then get back on the bus.

Before leaving, there’s one more angle.

The main hall again, this time from low down, a stone lantern in the foreground wearing a dense cap of moss. A single figure on the steps is about to enter, caught mid-climb. It’s not a grand shot. But it feels honest: one person approaching, everything else watching quietly.

Swan Lake Under a Volcano

The water at Lake Yamanaka feels wider than it looks on the map.

From water level, the lake stretches out in a low circle of blue and Fuji rises behind it like a white sail someone forgot to pull down. In this frame, swans and ducks scatter across the foreground, bodies tucked into the small chop of the surface. A swan curves it’s neck toward the camera as if it’s used to people standing a little too close.

Lake Yamanaka is the largest of the Fuji Five Lakes and has picked up the nickname “Swan Lake” because of the flocks that winter here; local tourism pages lean into the pairing of birds and volcano as a signature scene.

From the shore, the mood changes.

There’s a line of people standing along the rail, bicycles leaned casually against it, everyone facing the water. Some have their phones up, some are just standing there with their hands in their pockets, squinting into the light. On the road behind them, nothing much happens. Cars pass occasionally. Shadows fall long on the asphalt.

It’s not a postcard moment in the usual sense, but it does say something about the place. This isn’t an attraction you rush through. You come here to do exactly what these people are doing: look, adjust your coat, maybe complain about the wind and look again.

Further around the lake, you start to feel Fuji playing with reflection.

Strictly speaking this is Oshino, not Yamanaka, but the effect is similar: the mountain reflected in a narrow pond, houses clustered around it, an orange car thrown into the scene like a punctuation mark. The water is still enough that Fuji appears upside down with surprising clarity. It’s almost more convincing in the reflection than in the sky.

The official travel sites talk about how sunsets here dye the whole area red, how the collaboration of lake and mountain creates “breathtaking views.” That’s not wrong, exactly, but what I remember is quieter: the way the clouds moved slowly over the summit while everyone along the rail shifted their weight from one foot to the other, waiting for the light to do something worth photographing.

On paper, this is a scenic highlight. In reality, it’s an exercise in standing around together, watching a mountain refuse to hurry.

Water That Took Twenty Years to Arrive

The water in Oshino Hakkai looks exaggerated, like someone slid the saturation too far to the right.

In the photo, the ponds are a deep, luminous turquoise, so clear you can see down to the rocks and plants on the bottom. Wooden bridges cross the channels, connecting small islands of thatched-roof buildings and walkways. Fuji stands in the background again, more observer than centerpiece this time.

Oshino Hakkai is a cluster of eight spring-fed ponds in a village between Lake Kawaguchiko and Lake Yamanaka. The water here is snowmelt from Fuji that’s spent years some sources say up to two decades filtering slowly through layers of volcanic rock before emerging in these pools. The springs are recognized as part of the wider Mount Fuji World Heritage designation, but standing beside them, that’s the least interesting thing about them.

What draws your eye are the details.

On one side there’s a wooden waterwheel attached to a thatched building, the wheel frozen mid-turn in the image. To the left, a small waterfall spills down a rock face, half-framed by clipped shrubs. The path in the center pulls your gaze straight toward Fuji, as if the whole village has been arranged for that one sightline.

Another angle shows how people actually use the space.

Visitors walk along the paths, leaning on railings, pointing out fish in the water. There’s no single grand viewing platform; instead you get a series of small, overlapping perspectives bridge, porch, waterside rock each with it’s own frame of the mountain.

Inside one of the buildings, the focus shifts from landscape to objects.

Glass shelves hold an assortment of bowls, cups, lacquered containers, sake flasks. None of them are particularly rare, at least at first glance. They look like the things a family might have accumulated over decades: some chipped, some faded, some still bright. Open-air museums and folk villages all over Japan do this gather ordinary objects and give them room to be seen. It’s a quiet kind of preservation that fits this area, where the spectacular (Fuji, the springs) sits right alongside the everyday.

The same impulse shows up in a different way at Saiko Iyashi-no-Sato Nenba, the restored thatched-roof village on the shore of Lake Saiko a little further away. The official site talks about recreating the scenery of the original settlement, which was destroyed by a typhoon in 1966, with around twenty houses now used as craft studios, shops and small museums.

The village deserves it’s own space, thoug the steep roofs facing the mountain, the dark interiors, the display of old banknotes so I’ll come back to it properly.

For now, Oshino Hakkai lingers in my mind as a place shaped less by human hands than by time. Water that began as snow high on the mountain spends years underground, then finally arrives here, bright and cold, so clear you can see your hesitation in it.

A Village Rebuilt to Remember

Saiko Iyashi-no-Sato Nenba looks almost too composed at first glance. There’s Fuji again in the distance, but your eye gets caught before it reaches the summit by the dark triangle of a thatched roof, the circle of a waterwheel, a narrow path bending between low shrubs. On the left, a small waterfall drops neatly over rocks. Everything feels arranged, but not stiff.

This place is a reconstruction. The original Nenba village stood here on the western shore of Lake Saiko until a typhoon in 1966 destroyed most of it; decades later, the area was rebuilt as an open-air museum and craft village, with around twenty kayabuki houses turned into workshops, galleries and tea rooms.

You can feel that double life both memorial and tourist stop when you move in closer.

This isn’t a farmhouse or a museum room. It’s Maruten, the fried fish-cake stand, blue noren hanging across the top, glass counter full of skewers and oblong fritters. A man in a grey jacket leans in to order while another customer waits, hands in pockets. Above the counter, posters show idealized versions of what you’re about to eat. Below, the real thing sits under warming lights, a little more irregular, a little more human.

It’s easy to be cynical about villages like this the way they package the past into something consumable, complete with branded snacks and photo spots but there’s also something generous happening here. People who might never seek out a history book still end up walking under thatch, touching old beams, watching someone demonstrate a craft that would otherwise quietly disappear.

Inside the houses, it becomes harder to separate the staged from the real.

In one room, a dark wooden cupboard with sliding glass doors is filled with bowls and sake bottles. To it’s right, tall wooden slats filter the light from outside. An old wall clock hangs on a beam, face slightly yellowed, Roman numerals frozen at some arbitrary time. It looks exactly like the kind of object you find in your grandparents’ house not unique enough to be treasured, not worthless enough to throw away.

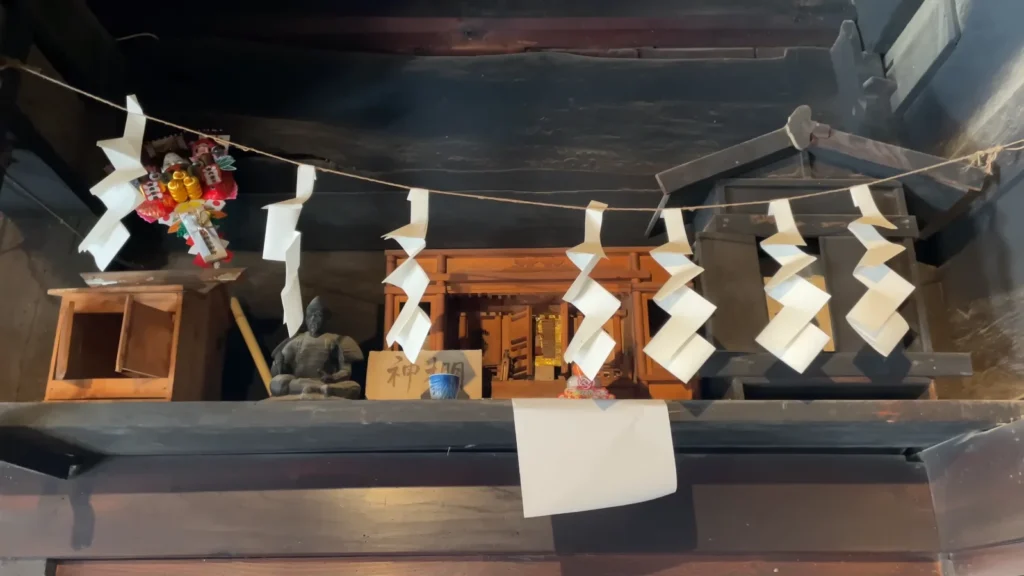

On another beam, higher up, the house shows it’s other function.

Here there’s a small kamidana, a Shinto household altar, sitting among other objects: a carved figure, a blue-and-white cup, a cluster of bright decorations on the left. A rope stretches across the space with paper shide folded and clipped along it. The ceiling above is darkened with age or smoke. Someone has propped a handwritten cardboard sign near the center. It’s not a grand shrine, just a small one, but it’s presence shifts the room from display into something that once held private rituals.

These interiors remind you that “traditional” doesn’t mean pristine. It means layers of faith, convenience, aesthetics, habit all stacked on top of one another.

Things That Outlast Their Owners

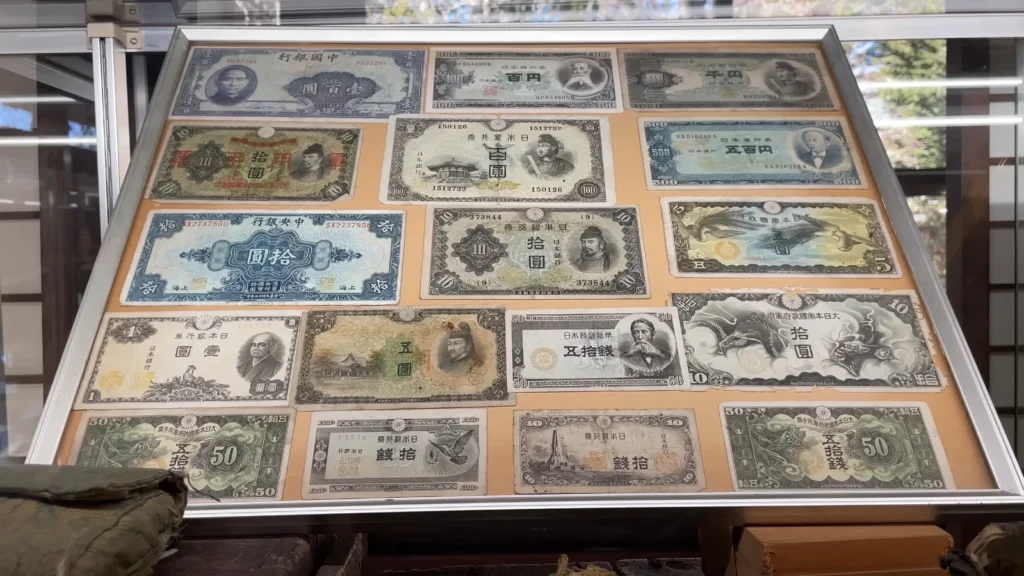

Money is one of the least romantic things in travel, but old money is different.

Behind glass, in a slanted display case, an array of Japanese banknotes spreads out like a carefully arranged fan. Some carry portraits in formal Western dress, others show temples, mythic creatures, ornate frames of vines and flourishes. The colors have softened over time muted blues, browns, faded greens but the designs still insist on being noticed.

These are the kind of notes that once passed quickly from hand to hand, folded into pockets, tucked inside drawers. Now they’re pinned in place, important not for what they can buy but for what they say about the years they moved through. You don’t need to understand the history of Japanese currency reforms to feel that shift; it’s there in the slight absurdity of looking at a wall of money that can’t be spent.

Back in Oshino, another glass case holds everyday bowls and cups.

The effect is similar but softer. Here the objects are more anonymous ceramics and lacquerware that might once have belonged to families whose names no one remembers. Together, these displays act as a counterweight to all the grand landscapes outside. Fuji will outlast everything. The ponds will keep filling and emptying. But these fragile things and the hands that used them, are what give the area texture.

Even the food, in it’s own way, joins this quiet parade of persistence.

We’ve already seen the ring of dango around the fire and the numbered skewers lined up at the stall, but there’s something about that numbering 1 through 6, taped a bit crookedly to the wooden rack that feels almost archival. Today’s order slips will be thrown away. The rack will stay, holding tomorrow’s skewers and the day after’s.

The same goes for the little restaurants and cafés.

The Park Coffee Stand, with it’s clean logo and blond wood interior, feels very contemporary. But give it long enough and the enamel sign will fade, the electrical cords will look quaint, the menu design will date itself. Someone decades from now might walk into a preserved version of it and think, So this is what early-21st-century lakeside coffee looked like

What Follows You Home

Days later, when I try to remember the trip, it doesn’t come back in order.

Sometimes it starts in the middle of Lake Yamanaka, with the swans drifting past and Fuji sitting there like a painted backdrop. The water has that particular winter shimmer bright but not warm and my hands are half-numb from holding the camera too long. The scene looks exactly like the brochures, which should make it feel fake, but doesn’t. If anything, it makes you suspect the brochures have been underselling it.

Other times the memory begins with the weight of the hōtō pot on the table.

The metal is hot enough that you keep your fingers on the handle for only a second at a time. Steam is drifting off the surface in soft, unfocused clouds. The noodles are thick and slightly clumsy, the vegetables cut into unapologetic chunks. It’s not delicate food. It’s the kind of thing you eat when you’ve been outside all day and you need to be convinced back into your body.

There’s also that quiet shot from Aokigahara that keeps reappearing.

Just a path and trees and air that looks as if it’s holding it’s breath. No mountain in sight, but you know it’s close. That’s how a lot of the Fuji area feels: not constant drama, but a series of small, ordinary scenes carrying the pressure of something enormous just offstage.

If someone asked what the region is “like,” I’m not sure I could answer in a clean sentence. It’s shrines that were once starting lines and are now quiet detours. It’s reconstructed farmhouses where the clocks have stopped but the coffee machines are new. It’s glass cases full of bowls and handwritten signs for shrimp rolls and the particular way light falls between cedars in the late afternoon.

Mostly, though, it’s that sense of being watched gently by the mountain from the end of a train track, from behind a station roof, from the far side of a lake where birds ignore it completely.

You come and go. Fuji stays. And after a while, that imbalance becomes comforting rather than grand.