Liberia’s not just some corner you’d skip over; it’s a gritty slice of West Africa with a past that hits hard and a culture that keeps it real. It’s parked along the Atlantic coast, squeezed between Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire, with Monrovia buzzing where the Mesurado River meets the sea. This place has a wild story, freed slaves from America setting up shop, local tribes holding their ground, and a toughness that’s seen it through wars and rough days. The culture’s a mash of rice dishes, mask dances, and songs that carry pain and pride, while its history as Africa’s first republic sets it apart. Let’s break down where it sits, what shaped it, and how its people keep their identity strong.

Highlights at a Glance

- Where It Sits

- Hills, Forests, and Wet Land

- Slave Roots and a New Start

- Tribal Crews and Their Ways

- Eats That Stick to Your Ribs

- Tunes and Moves with Soul

- Faith and Old Spirits

- Bouncing Back from Wars

- Gripping Liberian Spirit

- Chasing a Better Tomorrow

Where It Sits

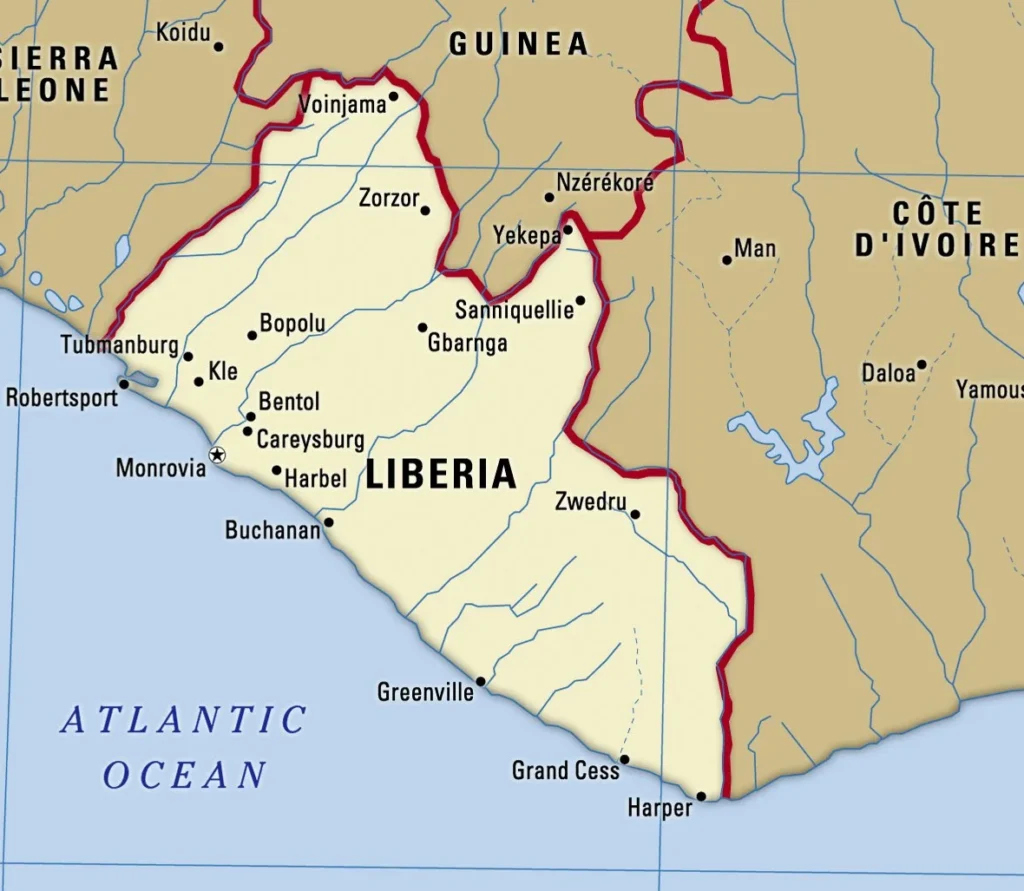

Liberia is located on the Atlantic coast of West Africa, covering about 111,369 square kilometers, not massive, but full of life. Sierra Leone borders it to the northwest, Guinea lies to the north, and Côte d’Ivoire stretches along the east. To the south and west, it meets the Atlantic Ocean. Monrovia, the capital, is right where the Mesurado River meets the sea, a perfect spot for ships to come in. The coastline stretches 579 kilometers, with sandy beaches and fishing spots, while inland it climbs into hills and thick bush. That location made it a landing point for traders long ago, and even now, it feels like a coastal hideout most folks miss.

Hills, Forests, and Wet Land

The land’s a mix of rugged beauty and hard living. The coast has sandy shores and lagoons, but head inland and you hit rolling hills, Mount Wuteve tops out at 1,440 meters, and rainforests that blanket 45% of the place. Rivers like the St. Paul and the Cavalla cut through, feeding farms and fishers. It’s hot and soaked, with rains from May to October dumping up to 4,500 mm in spots, turning roads to sludge. The forest hides chimps, pygmy hippos, and huge silk cotton trees, but it also brings malaria and floods. Farmers wrestle rubber and rice from it, and old trails still wind through for walking or trading.

Slave Roots and a New Start

Liberia’s tale kicks off with a twist. In the early 1800s, freed American slaves, around 13,000 by 1867, landed here, backed by the American Colonization Society, and set up Monrovia in 1822, named for President Monroe. They declared a republic in 1847, the first in Africa, with a flag ripped from the U.S. design. But the 16 local tribes, Kpelle, Bassa, and Gio, were already here, farming and trading, and clashes over land sparked tension. Before that, Portugal and Britain hauled slaves from the coast, and the new settlers’ arrival added a layer of friction that’s still felt today.

Tribal Crews and Their Ways

Liberia’s got 16 ethnic groups, each with their kick. Kpelle, about 20%, grow rice up north; Bassa fish and weave baskets in the middle; Gio and Mano, 15%, work iron in the east; Kru sail the coast. Americo-Liberians, from those settler days, add a Western edge, though they’re only about 5%. Traditions run deep, Kpelle’s Poro society does masked dances for men, Bassa women slap mud designs on walls, and Kru sing sea shanties. A handshake with a finger snap is a common greeting, showing respect across the board. That mix makes Liberia’s culture a tough, living thing.

Eats That Stick to Your Ribs

Food here is hearty and tied to the grind. Rice rules, eaten twice a day, jollof with palm oil and peppers, or with soup on the side. Fufu, a cassava mash, pairs with egusi stew from melon seeds and greens. Coastal spots serve smoked fish or crab stews, spiced with local heat. Cassava leaf stew, a fave, gets cooked with peanut butter and meat, taking time to prep. Meals are a group deal—big bowls with hands digging in, a village habit that’s stuck. Mangoes and coconuts pop up when ripe, a sweet nod to the land.

Tunes and Moves with Soul

Music here carries the weight. Highlife mixes guitar and drums from settler times, while palm-wine music, slow with string plucks, comes from Kru sailors. Tribal beats like Kpelle’s goblet drum power dances for harvests or initiations, often with masks jumping. Sande women sway in raffia skirts for rites. During the wars, songs like “Liberia, Sweet Liberia” kept hope alive. Now, kids blend old beats with rap, rocking Monrovia bars or village clearings, a sound of survival and pride.

Faith and Old Spirits

Religion’s a big player, mixing old and new. About 85% are Christian, Methodists and Baptists from settler roots, while 12% are Muslim, mostly Mandingo traders. Animism hangs on, with spirit worship in forests and rivers, strong in the bush. Lots mix it, church on Sunday, offerings for ancestors after. Churches and mosques share towns, and Christmas or Eid means shared plates. This blend came from trade and settlement, building a “do what works” feel that’s lasted through the mess.

Bouncing Back from Wars

Toughness is Liberia’s core. Two civil wars, 1989-1997 and 1999-2003, ripped it up, killing 250,000 and scattering half the people. Charles Taylor’s rebel chaos and warlord fights left Monrovia smashed, with kids turned soldiers. Peace hit in 2003 with UN troops, but Ebola broke out in 2014, taking 4,800 lives. Still, folks rebuilt, farmers replanted rubber, and women like Leymah Gbowee pushed peace, snagging a Nobel. That fight-back grit comes from a history of standing tall.

Gripping Liberian Spirit

Identity here is a survival badge. The flag’s red, white, and blue with a star yells freedom, a settler’s echo turned local. Kpelle and Bassa tongues mix with English in chatter, the official lingo. Names like Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the first boss, get streets and schools. The National Cultural Center hosts mask dances, and the diaspora, over 500,000 overseas, sends money back. Despite scars, there’s a drive to own the past, fueled by that war-toughened pride.

Chasing a Better Tomorrow

The future’s shaky but kicking. Roads and schools are rough, with only 48% literacy, but new builds are in play. Timber and rubber keep cash coming, and spots like Sapo National Park could draw visitors. George Weah’s 2018 win brought hope, though corruption hangs around. Young folks dream of jobs and calm, leaning on that war-hardened spirit to carve out progress, one step at a time.